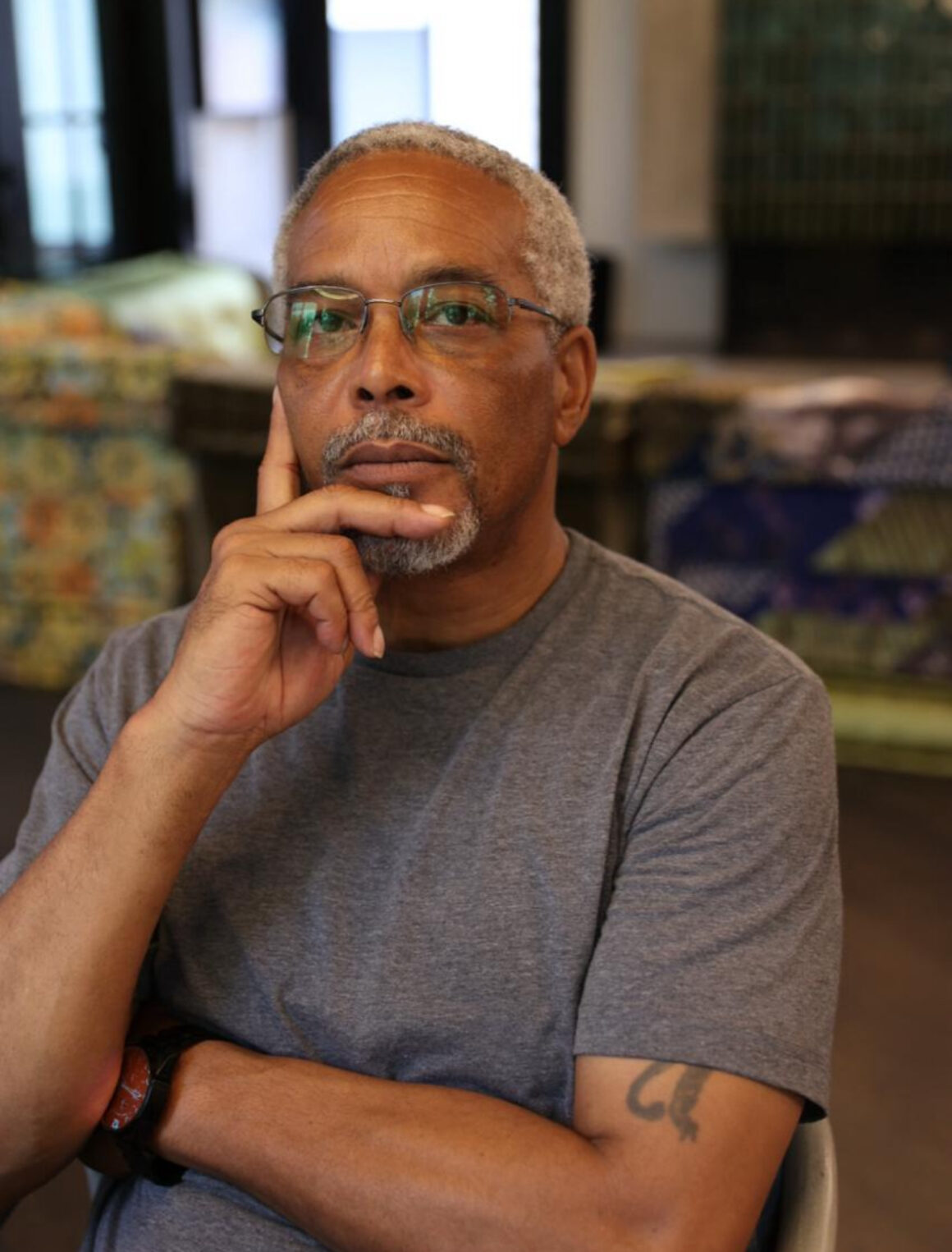

Canadian composer Wolfgang Webb returns with The Lost Boy—a luminous, late-night confession that blurs the lines between cinematic soundscapes and deeply intimate songwriting. Having spent years crafting music for television, Webb took a step back from the industry to rediscover his own voice—one shaped by insomnia, grief, and the slow, often painful work of healing.

In this candid conversation, Webb opens up about his creative rebirth, the emotional architecture behind The Lost Boy, and how making music became a form of therapy, reckoning, and release. From ghostly synths to orchestral flourishes, and from fractured relationships to fragile hope, this album isn’t just a return—it’s a reckoning with self.

We spoke with Wolfgang about his journey back to music, the emotional weight carried in his songs, and how silence, truth, and late-night solitude shaped one of the most quietly powerful records of the year

RM: First of all, Who is Wolfgang Webb?

WOLFGANG: I’m just an ordinary guy trying to figure it all out. I’m a composer from Canada, and music is how I make sense of the world—its chaos, its beauty, and all the spaces that connect the two. My music is grounded in storytelling—drawn mostly from real moments, and occasionally imagined worlds, or fragments in between.

RM: After spending years in television scoring and sound design, what motivated your return to music and the release of “The Lost Boy”?

WOLFGANG: I spent years scoring TV shows and crafting sound design for other people’s stories, but somewhere along the way, I lost my own. I was burned-out, depleted, and frustrated, so I stepped back from music entirely—just silence.

Honestly, I wasn’t sure if I’d ever come back to it. But one night, almost by accident, I found myself back in the studio. I started playing around and ended up writing a song called “BeforeYouSleep(ThePills).” It felt raw and unfiltered—something about it just clicked. Being honest, especially around mental health, felt necessary. I let it pour out.

That moment reminded me that the truth I’d been looking for in music had been there the whole time. It wasn’t about chasing a sound or a trend—it was about being real. That song became a turning point.

The music that followed became The Insomniacs’ Lullaby, and once completed— TheLostBoy. It was about returning to myself. Quietly, privately—writing in the middle of the night. That’s where these records began.

RM: How does your background in scoring influence your songwriting and the overall sound of your albums?

WOLFGANG: Scoring music to visuals taught me a lot—especially about silence, nuance, sonic build, and sound design. It trained my ear to listen differently, to leave space where space is needed, and to think of music as an emotional undercurrent rather than something that always needs to be front and center.

But the truth is, I wasn’t getting offered the kind of projects that aligned with what I really love —things with drama, warmth, intensity, and emotional complexity. Over time, I burned out— uninspired, exhausted, and honestly, a bit angry. I felt disconnected from who I was creatively.

It took a while, but eventually I came back to music with no agenda—just to see if I could reconnect with that original spark. That shift brought something important into my songwriting: the idea that it’s not about perfection, it’s about presence. Scoring taught me how to shape sound around feeling, and now that same instinct helps guide the emotional architecture of my songs.

So in a strange way, that chapter really prepared me for this one—to make music that breathes, that listens back, and that makes space for both silence and intensity to coexist.

RM: “The Lost Boy” delves into complex issues such as mortality and lost relationships. Can you share what inspired you to explore these themes in your music?

WOLFGANG: Once I finished The Insomniacs’ Lullaby, I realized I had a lot of inner-child work to do on myself. About three months later, I wrote the demo for “March”—which became the first video single on YouTube —and that track quietly set the tone for what was coming. It made me realize I still had things I hadn’t processed—grief, old patterns, inherited trauma—and I knew I needed to go deeper.

That became the heart of The Lost Boy. The record explores what it means to heal when closure isn’t possible—when someone you love can’t meet you where you are, can’t be accountable or take responsibility for the hurt they’ve caused. That kind of distance can be incredibly painful, and I wanted to give voice to that experience in a way that felt honest.

I also came to understand that closure in some relationships—especially ones shaped by narcissistic behavior—isn’t something you’re ever going to get in the traditional sense. You can’t reason with someone who refuses to acknowledge their role in the damage. You can’t build trust with someone who avoids accountability or turns your response to the harm into the actual problem. That realization was heartbreaking. But it also became strangely clarifying.

So much of The Lost Boy was written as an attempt to untangle that—to metabolize the silence, the gaslighting, the emotional erasure. Through the act of writing, singing, and producing, I found my own form of closure. By the time I finished the record, I realized something that changed everything for me: the lack of respect was the closure. The absence of care, the refusal to say sorry, the unwillingness to meet me in truth—that was the answer. And once I accepted that, I stopped waiting for an apology that was never going to come.

Instead, I let the songs carry it. I let the melodies hold the weight of the conversations that never happened. And in doing that, I gave myself permission to release it. That’s what this record really is: not just an album, but a letting go.

RM: You mentioned crafting your songs during late-night hours. How does this time of day influence your creativity and the emotional depth of your lyrics?

WOLFGANG: Nighttime is where I feel safest to explore. There’s a stillness that settles over everything after midnight—it’s like the world exhales. That’s when I can actually hear myself think. No interruptions, no noise—just this open space where emotions can rise to the surface without resistance.

There’s a kind of frequency you can tune into when the rest of the world is asleep. It’s subtle, but it’s powerful. The distractions fade, and you can access parts of yourself that stay hidden during the day. That’s when the most honest lyrics tend to show up for me—those fragile, complicated truths that only reveal themselves when you’re not trying to force anything.

That’s how most of The Lost Boy was created—between midnight and 5 a.m. I’d sit with a melody, close my eyes, and just let the feeling guide me. There’s something incredibly cathartic about writing when you’re half-dreaming—when the internal censor is quiet and memory and emotion start to blend. It’s almost meditative. Some of the songs felt like they were already there, just waiting for me to be quiet enough to hear them.

RM: Can you walk us through your songwriting process for a track like “Is It OK To Fall?” and how it came together?

WOLFGANG: “Is It OK To Fall?” came together quickly at first—almost effortlessly. The demo, melody, and lyrics were written in just a few hours. It felt emotionally clear from the start—one of those latenight writing sessions where the vulnerability just showed up and I let it move through me.

But production-wise, it ended up being more challenging than a lot of the other songs on the record. At first, I thought it was just a mixing issue. The song was technically finished and mixed —beautifully, by Andrew Lauzon—but something still didn’t sit right with me. I ended up pulling it off the record, which I think confused Andrew at the time. But it had nothing to do with his work—it just wasn’t landing emotionally, and I couldn’t let that go.

There was this answer-back guitar melody stuck in my head that I hadn’t included yet. I knew it needed a specific tone—something emotional, a little jagged, with that “drippy” texture close to Robert Smith’s guitar setup. So I reached out to Mark Gemini Thwaite and sent him the track, along with me literally singing the guitar part. It was very specific.

He sent it back and offered a few options, but I knew immediately when I heard it—this was the missing piece. No changes needed. He nailed it.

A few months later, we decided it would actually be a single off the album, and we ended up making a video for it too. It’s funny how something that almost didn’t make the record becomes one of the defining moments. Sometimes, you just have to trust that your gut knows before your brain catches up.

RM: The album features a unique blend of Kraftwerk-inspired electronics and orchestral elements. How did you go about creating this rich tapestry of sounds?

WOLFGANG: This has always been where my heart is. I’ve always had a love for electronica—it’s a space I feel really comfortable playing in. There’s so much freedom in shaping sound from scratch, manipulating texture, and building mood with synths and subtle pulses. I’ve always found ways to incorporate it into my music because it lets me express things that words alone can’t reach.

But I also have a deep love for classical and cinematic instrumentation—strings, brass, piano, all of it. There’s something timeless about those sounds. They carry an emotional weight and warmth that can ground the more experimental elements.

When I was building The Lost Boy, it was never about picking a “style.” It was about asking, what does this emotion need? Some tracks needed the intimacy of a single cello line; others needed the icy pulse of a vintage synth. Sometimes they needed both, side by side, speaking to each other.

What holds it all together is intention. Every sonic choice had to serve the emotional core of the song. That’s the thread that runs through the album—whether it’s a ghostly ARP sequence, a crushed drum loop, or a trumpet swell drifting in from somewhere half-remembered. It’s about creating space where contrast doesn’t feel like contradiction, but like conversation.

RM: What was it like collaborating with esteemed producer Bruno Ellingham, on “The Ride” and “March” and how did his influence shape the sound of “The Lost Boy”?

WOLFGANG: With “The Ride,” I remember playing Bruno a version that I loved, but it just lacked intimacy. I couldn’t quite find the words for it, but I wasn’t connecting to the intention of the song anymore. It felt emotionally distant. But Bruno heard something else in it—he layered a VCS3 ARP synth over my original parts, and suddenly there was this beautifully analog, slightly crunchy texture that gave the track a whole new life. It was unexpected—in the best way.

Then he programmed the drums from the ground up, and that was a turning point. It suddenly had more movement, space, and shape. After that, I actually went back and re-recorded my vocals—something I rarely do—because the new sonic bed gave me a different feel to sing from. Also, my original vocal was really low and sad, and that’s not where I wanted the song to live. I wanted it to rise, not sink. So I re-sang it.

He also mixed “March,” and his approach brought out the full cinematic potential of that track. “March” carries a lot of emotional and symbolic weight, and it needed space to breathe. Bruno was able to enhance that atmosphere without ever crowding it. He has this ability to make a track feel both expansive and personal at the same time—and that’s exactly what these two songs needed.

RM: What was your vision for the lead single “March,” and how do Esthero’s vocals complement your narrative as the “lost boy”?

WOLFGANG: “March” was one of the earliest songs I wrote for The Lost Boy, and it quietly set the emotional tone for the entire album. From the start, I knew it wasn’t going to be a conventional lead single —it’s not flashy or immediate—but it carried something deeper: this quiet persistence, this sense of movement without resolution. That’s why it’s called “March.” It’s about emotional survival, and walking forward.

I knew I was looking for the voice of an angel to help guide the lost boy. Esthero has one of those rare voices that feels angelic and fragile, and at the same time—strong AF. Her verse needed to add a sense of light and clarity, and it did exactly that. Her ad-libs—these dissonant, spectral harmonies—are absolutely gorgeous. Her voice paired with the lyrics felt like the sound of wisdom itself. Where my vocal feels weighted and human—like the “lost boy”—hers feels like it’s reaching from somewhere beyond. Like a guide, or a memory, or the part of us that already knows we’ll be okay.

I also have to acknowledge the incredible Carmen Elle, who sang the vocal chants with me at the halfway point of the song—her voice brought a grounding warmth that carried so much emotional weight.

And while I’m talking about “March,” I need to give credit where it’s due. Bruno Ellingham brought such clarity and atmosphere to the track in the mix, Larry Salzman added his signature brilliance on drums and percussion, and John “Wheels” Hurlbut came up with a beautiful vocal effect on Carmen’s part that gave it an ethereal lift.

The video for “March” was something I’d been planning from the beginning. I kept sketching out ideas—pathways, stone angels, castles, ruins. But I hit a wall creatively, and that’s when I teamed up with Shauna MacDonald, who ended up co-directing all four of the album’s videos with me. Shauna has this uncanny ability to translate the emotional core of a lyric into visual language. For her, “March” was a song of hope—a visual lifeline, a reminder that even in deep isolation, we still belong to something bigger.

Kristjan Viger also played a huge role—he filmed the footage of me singing and created the candle flares. He was also my co-creative on three of the music videos from my first record, so there’s a shared language between us. And then there’s Patrick Tiberius Gehlen, a longtime friend and VFX artist, who brought the statues to life in such a haunting, beautiful way.

The end result is a piece that lives in that delicate space between desolation and grace—just like the song

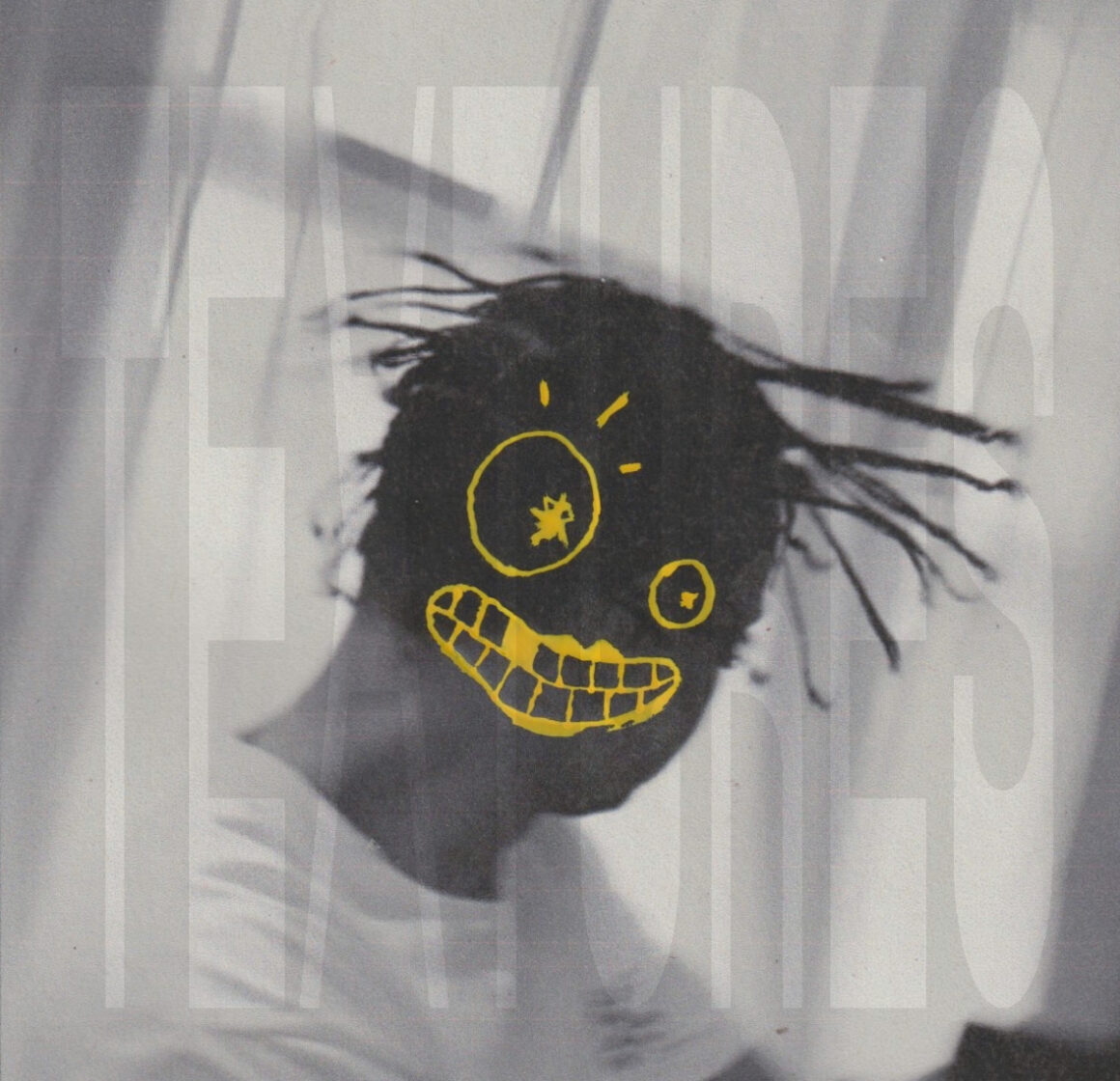

RM: The album artwork visually represents the journey of the “lost boy.” Can you discuss the significance of this imagery and how it relates to the themes of the album?

WOLFGANG: I came across this incredibly talented artist—Blatta (@blatta_art on Instagram)—and their imagery immediately resonated with the songs I was working on. Honestly, I got lucky discovering them. The moment I saw their work, I knew it would be a perfect fit for The Lost Boy. I was about three-quarters of the way through recording the album at the time, and I already knew that was going to be the title.

I sent them a few demos, and we stayed in touch throughout the process. What amazed me was how instinctively their visual world aligned with the emotional tone of the record. I didn’t have to over-explain anything—they just intuitively understood the atmosphere I was trying to create.

Their imagery graces the front cover, which I see as the “lost boy,” and a second piece for the inside artwork, which I think of as “the found man.” That contrast felt essential. The album is a journey—from disorientation and emotional fragmentation to a kind of quiet reckoning. The “lost boy” reflects that raw, searching place, and the “found man” represents someone who’s been changed by the process—not fixed, but aware, grounded, more whole.

The artwork gives the record its emotional framing. It invites the listener into the themes of grief, resilience, memory, and transformation—before they even hear a note.

RM: How important do you think visuals are in complementing music, especially with an album as thematically rich as “The Lost Boy”?

WOLFGANG: I’m a visual thinker. I see colors, scenes, and textures when I write music. It’s almost like scoring a film that hasn’t been made yet. Every sound suggests a certain image or atmosphere to me—sometimes a ruined landscape, or just a shade of grey that won’t let go.

If I had unlimited time and resources, I’d create a visual world for every track. That’s how important visuals are to me—they don’t just complement the music, they extend it. They offer a second layer of meaning, a deeper emotional entry point.

With The Lost Boy, I kept coming back to the idea of quiet beauty in decay. There’s something haunting and strangely hopeful about abandoned places—cracked concrete, rusted metal, overgrown ruins. They’re reminders that no matter what we build or abandon, life finds a way.

Nature pushes through, fills the voids, reclaims her space. That symbolism runs through the entire album.

In the videos we created—especially for “March” and “The Ride”—we leaned into that aesthetic. The visuals became emotional landscapes: part memory, part dream, part disappearance. They help express what the lyrics sometimes can’t—the unsaid things, the atmosphere of loss or resilience that lingers in silence.

When I envisioned “Clap,” the image that kept returning to me was fireflies drifting above dry grass and scattered stones in a quiet desert. Something barely alive, but still glowing—fragile, flickering, and persistent. That visual captured the emotional undertone of the song perfectly: this sense of quiet resilience, of holding on to light even in the most desolate places.

There’s something hauntingly beautiful about that contrast—how even in the emptiest landscapes, there’s still a pulse, a shimmer, a breath. To me, music and visuals are part of the same emotional language. One speaks through sound, the other through space and light—but when they meet, something deeper happens.

RM: What do you hope listeners take away from “The Lost Boy,” especially when confronting their own struggles?

WOLFGANG: The Lost Boy is about wandering through emotional wreckage, memory, and time—and somehow finding your way through the quiet. It asks: what’s left when you’ve lost your sense of self? And what still pulses underneath it all? For me, the answer was nature, and truth— something raw and undistorted. The record is about trying to reclaim those things, even when you don’t feel ready.

There’s a deep emotional architecture running through these songs—whether it’s a ghostly silhouette in a video, the atmospheric space between cello swells, or an unguarded lyric. I wanted to create a space where pain, beauty, grief, and renewal can all coexist. Not to fix things, but just to hold them for a moment.

My record doesn’t offer answers—it offers presence. A quiet reminder that even in disintegration, there’s dignity. Even in silence, there’s strength. And even when we feel lost, we’re still connected to something greater—nature, memory, frequency, and the quiet force of the human spirit.

If someone listens to this album and feels a little less alone in whatever they’re carrying, then it’s done what I hoped it would.

RM: In what ways do you believe your music can provide solace in the shared experience of being human?

WOLFGANG: I think music can be a kind of emotional mirror. Not to reflect back the perfect version of ourselves, but to show us who we are when we’re raw, uncertain, or quietly holding something we haven’t yet put into words. That’s the space I try to create with my music—a space where people feel like they’re not alone in their mess, their grief, their questions.

With The Lost Boy, I wasn’t trying to preach or prescribe anything. I was simply trying to be present with what’s hard to hold: loss, unresolved relationships, the heaviness of inherited trauma, and the strange, slow work of healing. I think that honesty—when it’s offered without spectacle—can be comforting in its own way.

Sometimes solace isn’t about being uplifted—it’s about being understood. Knowing that someone else has walked through a similar dark place and turned it into something tender, something listenable, something true. I hope this album reminds people that they’re not broken for feeling deeply—that it’s okay to be undone for a while. There’s strength in staying with the feeling, and sometimes, that’s where the healing starts.

If my music can be a soft place to land in the midst of that, then I’m grateful.

RM: Following the release of “The Lost Boy,” what can fans expect next from you? Are there any upcoming projects or performances on the horizon?

WOLFGANG: Right now, I’m honestly consumed with having meaningful conversations like this one. They help me reconnect with the why behind the work, and give the record a second kind of life.

I’m also in the final stages of wrapping up edits for the fourth music video from The Lost Boy, for the track “Clap.” The concept is very simple: fireflies above dry grass and stones in a desert—a fragile, flickering hope in an otherwise desolate place. Something barely alive, but still glowing. That visual felt like the emotional undertone of the track itself—this tension between emptiness and persistence. And like much of the album, it’s rooted in extreme nature—the quiet power of the earth reclaiming space.

The reprise version of “Clap” closes out the record, but the video-version—with me singing —feels like a kind of bedtime tale. It carries this gentle encouragement, like it’s being sung by the older, wiser version of the boy on the cover. A version that’s lived through the wreckage and come out the other side with a little more light.

It’s a voice that says: “We’ve gone through all these failures, and here we are, still looking up at the sky. And because we’re together—you are not alone.”

That framing actually came from my co-creative collaborator Shauna MacDonald, who’s worked on all the videos with me. A few months ago, she said, “You know, this song is a bedtime tale,” and I just paused and said, “You’re right.” That’s exactly what it is. Quiet hope in the dark.

As for what’s next—there’s always more music in me. But right now, I want to give The Lost Boy the space it deserves, and let these final visual pieces help carry it the rest of the way.

RM: How do you see your artistic journey evolving in the future, especially after this creative rebirth?

WOLFGANG: That’s an amazing question. I only intend to write music that’s created inside the moment. That’s the commitment I’ve made to myself moving forward.

The Lost Boy and The Insomniacs’ Lullaby marked a return to honesty—for better or worse. They were born from stillness, insomnia, grief, reflection… but also from presence. And that’s the space I want to keep creating from. I’m not interested in chasing what’s next—I’m more focused on staying open. Open to whatever arises, whatever feels true.

When it comes to the future, I have no map. I’m not pursuing the next album, but I trust it will find me when the time is right. What I do know is that I want to keep working from a place of integrity, intimacy, and instinct—whether that’s through music, visuals, or collaborations that push me into new territory.

This isn’t about momentum—it’s about meaning. And as long as that’s what’s guiding the work, I know I’m exactly where I’m meant to be.

Wolfgang Webb’s The Lost Boy is a hauntingly beautiful meditation on grief, healing, and emotional reckoning. With cinematic depth and raw vulnerability, Webb transforms silence into song, crafting a sonic world where pain and resilience coexist. This is more than an album—it’s a quiet act of survival.”