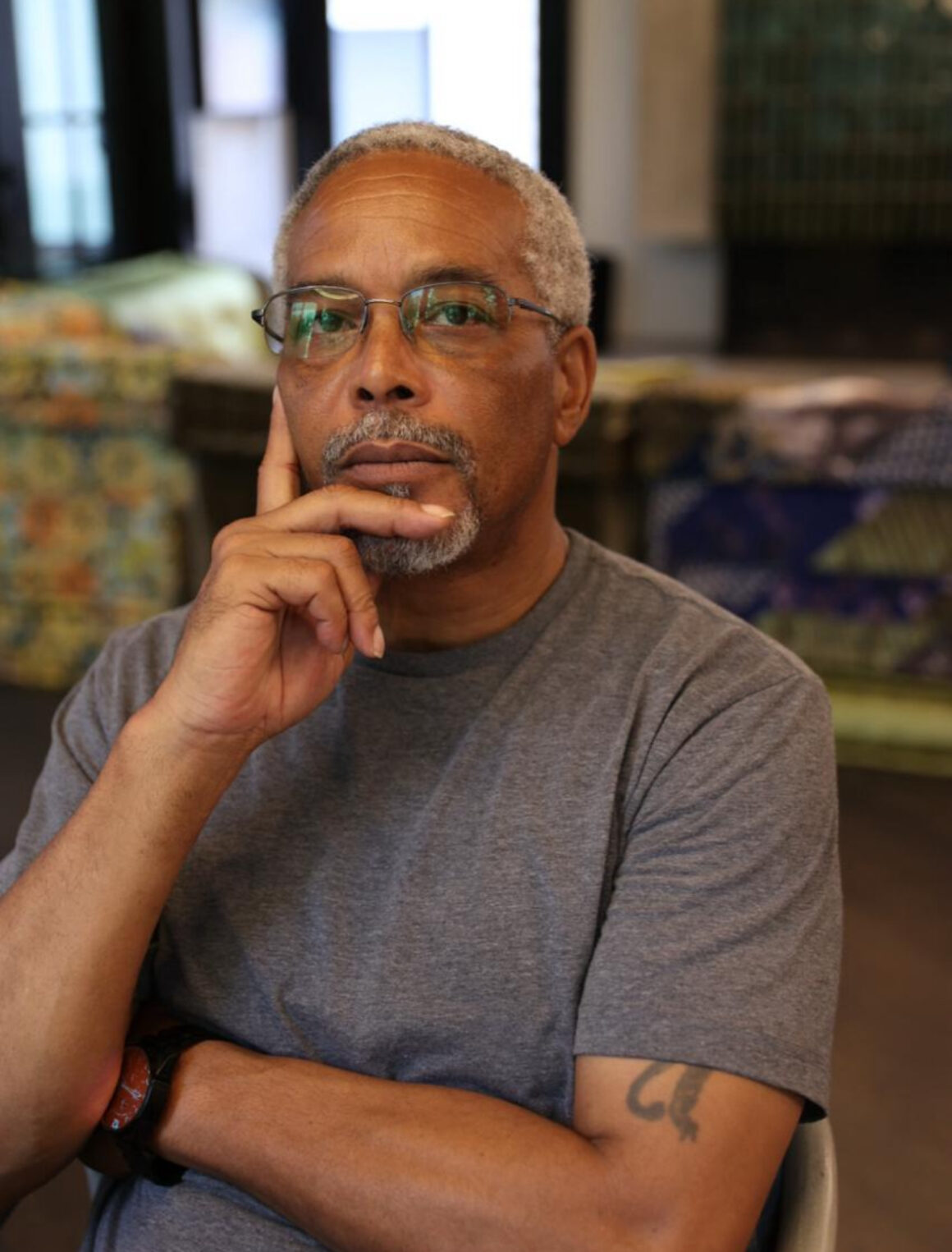

Best known for her powerful presence as a fiddler, composer, and arranger with the legendary Irish band Kíla for over three decades, Dee Armstrong is a singular creative force deeply rooted in the mythic and musical traditions of Ireland. A self-taught multi-instrumentalist and community arts worker, Armstrong has spent her life channeling ancestral echoes, lived experiences, and wild inspiration into richly evocative soundscapes.

Her latest solo album, Deichtine’s Daughter, is a spirited, soul-stirring journey that weaves personal history with ancient myth. Imagining the untold story of a forgotten heroine from Irish lore—Deichtine, the mother of Cúchulainn—Armstrong gives voice to the silenced, the invisible, and the visionary. Blending original compositions with select traditional pieces, and featuring contributions from her own sons, Deichtine’s Daughter is as much a family heirloom as it is a cultural offering.

In this candid conversation, Dee Armstrong reflects on the roots and rhythms of her music, her creative process, the wild beauty of North Leitrim, and the enduring power of music to tell stories where words fall short.

RM: First of all, Who is Dee Armstrong?

D A: I am a self-taught musician, playing fiddle, viola, hammer dulcimer, bodhran, tuned percussion. I am mainly known as a composer, arranger and fiddle player with Kila for the last 34 years. I also play with Freespeakingmonkey and The Armagh Rhymers.

Several generations of my family were and are musicians. My grandmother Maggie Armstrong was a great singer and storyteller who sang old traditional and gospel songs. My father was taught traditional and classical music by Derek Bell of the Chieftains and my mother was a brilliant classical piano player and teacher. Many cousins and my sister all play. My four children play and /or sing. I also make massive willow puppets and structures for carnivals and am a community arts worker. I run a Rockschool for kids aged 10 to 18, where kids learn to play in bands, write their own songs and perform gigs and record.

RM: Deichtine’s Daughter is a fascinating title with deep mythological roots. What drew you to the idea of imagining Deichtine’s daughter, and how does that theme carry through the album?

D A: Deichtine was the mother of Cúcullin, one of Irelands great mythological heroes. Deichtine means “Ten Fires” in Irish as a literal translation and I loved that. However we know much more about Cúcullin than Deichtine and this is often a recurring theme in Ireland. Women get written out of history. What if Deichtine had a daughter, or Cúcullin a sister, what would she have been like? Louis de Paor was asking that question to himself, and then he saw her…walking down the road in Galway, swinging a hurl…and she made such an impression on him he wrote a poem for her.

RM: How did Louis De Paor’s poem influence your songwriting process for the title track?

D A: The poem hit me immediately ..it was more a feeling than anything…of strength, having a voice, fighting for your rights, fighting for your life. Fire and inspiration. So the piece of music says that to me. It’s an expression of that.

RM: Your music is rooted in both personal and cultural history. How do you balance storytelling with musicality when crafting your songs?

D A: I write intuitively, I don’t read music very well and I learn tunes by ear, do string arrangements by ear, and use the recording process to arrange music usually as I can’t write it down. It’s all in me head. Tunes usually pop into my head as I am sitting playing the fiddle or banjo or whatever. They express whatever is going on in my life at the time I guess. I try not to get in the way and let it happen. My sons will tell you, I don’t like doing more than one or two takes often… I like catching the initial spirit of the piece. Music is an amazing communicator. The feeling of the story is there, as I write tunes and music, there are no words. I often focus on the atmosphere of a piece of music..whats coming through..emphasise that.

RM: Your family’s musical legacy is evident in this album, especially with your sons Diarmuid and Lughaidh contributing. What was it like working with them in the studio?

D A: Plenty of craic and door slamming! We are all quite particular, but generally we all get on great. We have a similar musical sensibility I think. Lughaidh and I have been working on soundtracks and stuff for theatre since he was about 14 or 15. He’s a very gifted musician. We both love creating atmospheric soundtracks, and indeed I think this is a shared composing trait with us… there is a visual element, we are painting a picture. Diarmaid is a dancer and he brings another angle into it all with that. We all have a zany imagination and made strange little short films over lockdown!

RM: Do you see the next generation of Armstrong musicians continuing this tradition?

D A: They already are! My daughter Rosie is a lovely singer, and my other son Tiggy plays bass. His son, my wee grandson Leon, is very musical …he sings away. Sur,e who knows what will pop out? Music is my anchor, and it will probably be theirs.

My cousin Bridget is a great musician and her kids are all musical, and so it goes. If there is a love for it, it will probably continue.

RM: How has your upbringing in a musical family shaped your approach to music today?

D A: Well I didn’t want to play music I wanted to be a dancer! So I didn’t play as a kid and came late to the party. My parents tried to get me to play fiddle and I got a few lessons from an amazing fiddle player Mary Gallagher, but I just wanted to dance. I was into Heavy Metal, Rock, Disco and Funk as a teenager. I never imagined I would play traditional music …but it was always there in the background, especially the Chieftains as Derek Bell would come and make reeds with Dad and we would visit Paddy Maloney sometimes. I took up fiddle age 16 or 17, then had a baby, so it wasn’t till I was 19/20 that I took up learning tunes properly.

RM: Many of your tracks have deeply personal stories behind them—The Prince of Laughter, Boihy Mountain Road, and Ed the Visitor, for instance. Do you find it challenging or cathartic to translate such personal experiences into music?

D A: It depends on the tune. Often Ill write a tune for a person, as in The Prince of Laughter, or one of my children, as in Django’s …Ed the Visitor is for our legendary dog Ed who was a constant companion through times good and bad. It’s not challenging really it’s just kinda lovely.

RM: The Killi Willi Waltz has such a wild origin story—waking up on a bar floor, dreaming of a tune! Do melodies often come to you in unexpected moments like that?

D A: Hahahaha! Well that was funny…I wonder was it the shit loads of B52s I had consumed the night before! Luckily I crawled over to the fiddle and managed to extract the tune to the fiddle before I forgot it! I have dreamt other tunes but they have slipped away. I think the best tunes come to us in unexpected moments. Wandering down the road, after chatting to a friends, while trying to learn a tune, after a good shag…you just never know.

RM: Frailach highlights the power of music across cultures. Why was it important for you to include this particular piece in your album?

D A: Well, Im a huge fan of Roma gypsy and Irish Traveller music, also Middle Eastern music, Jewish Music. Nomadic people carry the music with them, absorbing everything they hear and turning it into their own versions of gold. Often the most powerful music comes from the most oppressed. Look at the history of the Blues. The experiences of the people live in the music. Music is the lifeline…it can’t be taken away, and then it speaks to us down through the generations. We are witnessing the attempted obliteration of Palestine and the Palestinian people currently. So many Jewish people have spoken out against this genocide as it is a repeat of their own suffering. This tune is for them and the people of Palestine and their children, who suffer occupation, death, starvation and destruction every day.

RM: Your album blends original compositions, traditional tunes, and collaborations. How do you decide which songs make the cut?

D A: The album is made up of all original compositions bar Frailach, and Yon Do, which is a traditional Selkie song from Scotland. I just liked the combination and I wanted them all to fit together and these did fit. I wanted it to be an album of primarily my music.

Eoin Dillon and I were playing a few tunes one day, and he wrote one part of the Bearna Waltz. Bobby Lee wrote Prince of Laughter together… he wrote the chords and I wrote the tune and strings.

RM: Your home in North Leitrim seems to have a strong influence on your work, with tracks like Birch Wind and Boihy Mountain Road. How does the landscape and history of the region shape your music?

D A: It’s a very wild and beautiful place … up until the 50s and 60s there were 158 families living in this small townland, all with loads of kids. They nearly all had to emigrate because the land was poor and it was too hard to make a living. This always resonated with me, and it’s so sad that this had to happen. There were lots of music on the mountain and musicians. The place just resonates with me somehow.

RM: You’ve mentioned playing with musicians like Dave Donahue in your early days. How has the Irish music scene changed over the years, and what excites you about it today?

D A: Dave Donahue was a great friend of mine. May he rest in peace. The main thing is that you could get a bedsit or a small flat in Dublin in the 80s and 90s for 12 or 15 quid a week. If you had little money you could live in the middle of town where all the action was. You could go busking, go to sessions, meet other musicians and walk home. I had a young baby as a teenager so I was lucky to live with my friends on Wexford street and they helped me with the baby. Otherwise I would have been very isolated. The scene in Dublin was buzzing…that’s where I grew up. This Lizzy, Sinead O Connor, Dolores O Riordain and the Cranberries, U2, Aslan, Waterboys… so many more..there was a sense of excitement…so many great bands and a freedom of musical ideas across the board…traditional and folk included. Riverdance and Ireland getting in to the World Cup as well! All this meant a lot to us. Suddeny people across the world wanted to hear us. The Celtic Tiger didn’t do us any favours …no one can afford to live in the cities in Ireland now. If you don’t have affordable housing, musicians and artists, and ordinary people will have to leave, and the music scene will be dissipated. Luckily the folk and traditional scene is having a real revival in Ireland again…look at the wonderful Lankum, for example… brilliant to see. Im looking forward to getting out to a few gigs after being a single mum for years and years!!!

RM: If listeners could take away one feeling or message from Deichtine’s Daughter, what would you want it to be?

D A: That’s up to the listener!

RM: What’s next for you after this album? Any upcoming tours, projects, or collaborations we should look out for?

D A: I am just finishing a 13-date tour in Ireland to launch the album. I have more music recorded with my sons…music the three of us wrote together, and I am hoping to finish that off in the next few months. I’ll be playing festivals in Ireland in the summer, and we will see each other after that!!

Deichtine’s Daughter is more than an album—it’s a living, breathing tapestry of memory, myth, and music, stitched together by a lifelong artist whose creativity refuses to be boxed in. Dee Armstrong’s work bridges generations, landscapes, and genres, offering listeners a rare glimpse into the heart of Irish storytelling through sound. From bar floors to mountain roads, from family jam sessions to ancient legends reimagined, her music speaks with an authenticity and fire that is both timeless and fiercely of the moment. As the echoes of Deichtine’s Daughter continue to ripple outward, one thing is clear: Dee Armstrong’s voice—intuitive, bold, and rooted in something much deeper than notes on a page—is one we’re lucky to hear.